A viewing of Halloween at the end of October, Miracle on 34th Street in late December or Independence Day in early July will offer something very different than at any other time of year. The same applies to war epics such as writer/director David Ayer’s latest work, Fury.

Watching the film on Armistice Day 2014, marking a century and three months since the beginning of World War I, with a poppy through my coat, images of remembrance services held all over the Commonwealth fresh in my mind and in a mood of reflection and appreciation, the fear, brutality and sacrifice that was suffered by so many during the two great conflicts of the 20th century becomes all the more acute.

Fury is the story of an American Sherman tank of the same name and said tank’s crew, who call the cramped interior of its metallic shell home. We join them in April 1945 in a Germany under decree of ‘total war;’ every man, woman and child must defend the Reich from the advancing Allies and those who do not pay a high price.

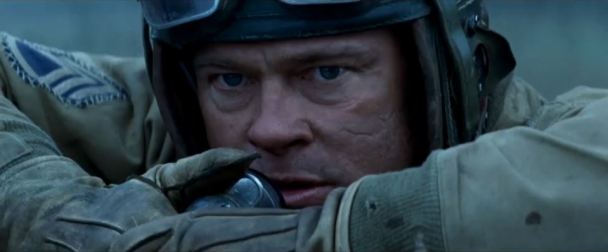

The silence of a misty, muddy, blasted wasteland of corpses and twisted metal is broken by the hoof-fall of a white horse, ridden by a high-ranking Nazi official. From nowhere, another figure knocks the German off his mount and stabs him through the eye – displayed with applicably gruesome and unerring close-up. The horse is set free and a relative calm falls over the scene once more. It is Brad Pitt’s appropriately nicknamed Don ‘Wardaddy’ Collier whom, unsurprisingly, we meet first. A character some way between his role as the elemental, passionate and fearless-in-the-face-grizzlies Tristan in Legends of the Fall (Edward Zwick – 1994) and the ruthless, determined, moustachioed Lt. Aldo Raines in QT’s Inglourious Basterds (2009), he is an enigmatic figure whose sole purpose seems to be killing Germans and keeping his own men alive. Simplistic? Yes. Realistic? Quite probably.

The silence of a misty, muddy, blasted wasteland of corpses and twisted metal is broken by the hoof-fall of a white horse, ridden by a high-ranking Nazi official. From nowhere, another figure knocks the German off his mount and stabs him through the eye – displayed with applicably gruesome and unerring close-up. The horse is set free and a relative calm falls over the scene once more. It is Brad Pitt’s appropriately nicknamed Don ‘Wardaddy’ Collier whom, unsurprisingly, we meet first. A character some way between his role as the elemental, passionate and fearless-in-the-face-grizzlies Tristan in Legends of the Fall (Edward Zwick – 1994) and the ruthless, determined, moustachioed Lt. Aldo Raines in QT’s Inglourious Basterds (2009), he is an enigmatic figure whose sole purpose seems to be killing Germans and keeping his own men alive. Simplistic? Yes. Realistic? Quite probably.

Fury’s other inhabitants are Boyd ‘Bible’ Swan (Shia LaBeouf), who obviously enough is the divine guiding light and moral compass of the group; Trini ‘Gordo’ Garcia (Michael Pena), the token Hispanic/Mexican; Grady ‘Coon-Ass’ Travis (Jon Bernthal), the token redneck neanderthal; and last but not least to complete the generic U.S. Army war movie quintet is Norman Ellison (Logan Lerman), a desk clerk taught to type 60 words a minute, not to kill Germans, who has only been in the army for eight weeks when he comes in to replace ‘Red’ – the very former front gunner who was blown to pieces, literally, in recent action.

From here, Fury follows the familiar template of inexperienced, fish-out-of-water, pencil pusher thrown into the action facing the various rites of passage that must be achieved to complete his arc from rookie to war hero in the space of two hours. Norman, or ‘Machine’ as he will belatedly be christened, is the only one of the cohort to undergo any kind of character transition and Lerman’s performance is commendable.

In its washed out palette of brown, grey and green and field by field, town by town action the film reminded me of the HBO series Band of Brothers, or even Saving Private Ryan (1998) but where Ayer’s film falls short of its post D-Day counterparts is its complete lack of character development. An audience watching Fury finds itself in a similar position to Tom Hanks/Captain Miller’s crew; we’d love to find out more about Collier, just as the men of Spielberg’s movie have a running bet as to who can find out Miller’s former profession, but little is offered. Fury falls short as a character study but does achieve it’s aims of being an unrelenting, visceral and at times brutally violent depiction of the Second World War.

Limbs, and even heads, are blown off in front of our eyes as the terrifying might of each forces’ tanks is put on show. The battle sequences between Shermans and Panzers are breathtakingly realistic and are a certain high-point of the film.

Very little quarter is offered to the Germans, other than as desperate cannon fodder, but a meal shared between Collier, Ellison and two Frauleins allows for some fraternisation, a quick shave, a plate of eggs and bacon, and a brief respite from the chaos of the world outside. One element of Ayer’s film which I did appreciate was the lack of glory, gloating or celebration that went along with the inexorable drive toward Berlin. I don’t believe I saw a single Star-Spangled Banner for the duration and that was a refreshing change that showed a reverence for the vanquished as well as the victorious. Rather than raise many a glass to the downfall of Hitler’s Germany, they do so to black out the atrocities they have seen and themselves committed which humanised men deadened and traumatised by their experiences.

The Butch and Sundance type last stand which fills the final sequence brings the action movie side of this production to its climax. It does not descend into anything like the farcical ending of Inglourious Basterds but given the lack of attachment between character and audience that has been generated it is hard to be too concerned about the fate of our war-weary crew. It is high adrenaline viewing nonetheless and there is space for yet another token character – the good German. What a relief.